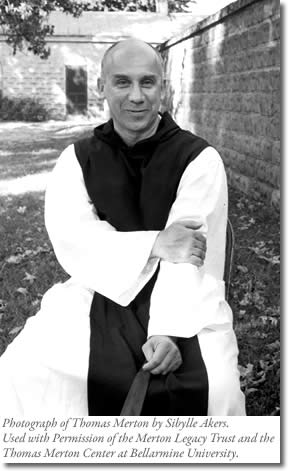

Thomas Merton

40 Years Later

Best known for his bold autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, Cistercian monk, trailblazing interfaith dialogue partner, and

best-selling author Thomas Merton died 40 years ago this month. On

December 10, 1968, he was accidentally

electrocuted while taking a

bath in Thailand, where he was

attending an

inter-religious meeting of

monks from around the

world.

Best known for his bold autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, Cistercian monk, trailblazing interfaith dialogue partner, and

best-selling author Thomas Merton died 40 years ago this month. On

December 10, 1968, he was accidentally

electrocuted while taking a

bath in Thailand, where he was

attending an

inter-religious meeting of

monks from around the

world.The Seven Storey Mountain was published in 1948, when Meron was only 33 years old. In those days, it was almost unheard of for a monk to write an autobiography. But throughout his life, Merton found it nearly impossible not to write about what was happening inside himself, even when he was in the cloister. Still, it was odd. Why would a monk—a man who has taken a vow of silence—publish? Monks were supposed to “die to the world,” which meant, they weren’t supposed to care about things like telling their story to an audience. But the book went on to become a best seller, and Merton wrote dozens of books over the next two decades.

Merton actually began his literary career at precisely the same time he began his monastic one. He was a poet and published two collections of poems with the independent publishing house New Directions, before The Seven Storey Mountain came out. New Directions was also publishing people like Ezra Pound, Henry Miller, and Dylan Thomas.

Merton was brash as a young man, the son of two artists. As a youth, he spent much of his time in Europe, returning to the U.S. in 1935 to attend Columbia University. In the summer of 1941, a few months before he became a monk, Merton was living in upstate New York teaching English at St. Bonaventure College. He was in his twenties and trying to figure out what to do—attracted to both the life of the mind (as a writer) and the life of the spirit (a possible, religious vocation). He would later say that he finally figured out who he really was while visiting a remote monastery in the hills of Kentucky. On his first visit as a retreatant to the Abbey of Gethsemani, during Holy Week of 1941, he wrote in his journal, “I should tear out all the other pages of this book and all the other pages of everything else I ever wrote, and begin here.” And so he went there, and stayed.

In The Seven Story Mountain, Merton described the day he entered the monastery to become a monk:

“Hullo, Brother,” I said.

He recognized me, glanced at the suitcase, and said: "This time have you come to stay?’"“Yes, Brother, if you’ll pray for me,” I said.

Brother nodded, and raised his hand to close the window.“That’s what I’ve been doing,” he said, “praying for you.”

So Brother Matthew locked the gate behind me and I was enclosed in the four walls of my new freedom.

The tensions that surfaced in Merton’s life and work made his writing all the more relevant to millions of readers long after his death in 1968. Many of us bump up against the same questions that filled his books, namely, how do we dismantle our “false self” and gradually discover our “true self”?

He was hounded by admirers throughout the 1960s. Oftentimes, he enjoyed the attention, but he also yearned for greater silence and considered the possibility of leaving his monastery altogether and founding a hermitage in some remote place. He once wrote, “An author in a Trappist monastery is like a duck in a chicken coop. And he would give anything in the world to be a chicken instead of a duck.” Yet Merton was full of contradictions, and he continued to write and express himself to millions of people beside his monastic brothers.

Merton’s genius was in showing those of us outside the monastery how to live more like we are on the inside. Some of his monastic brothers resented him for this. But Merton was committed to distilling the monastic life to the point where it seemed possible to replicate it in the secular world. Prior to Merton, monasticism was perceived as a life of retreat, irrelevant scholarship, and prejudice against the world. After Merton, to live like a monk became synonymous with mindfulness, attentiveness, contemplation, and embracing others.

During December, numerous events are scheduled in remembrance of the life and works of Thomas Merton. The Thomas Merton Center in Louisville, Kentucky, lists events taking place throughout the U.S. and in several countries around the world. Included is a talk by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, at St. Cyprian’s Church, London. Visit the center's website to find out what's happening in your area.